Prague, The Threshold

1911-1927

Prague, The Threshold

1911-1927

Mahler’s departure from Vienna was probably one of the reasons that Zemlinsky also left the city. Zemlinsky’s second opera, Der Traumgörge (George the Dreamer), in which the hero’s village recalled the atmosphere of Leopoldstadt, was scheduled for a premiere at the Hofoper on 4 October 1907, but was compromised by Mahler’s resignation just two days earlier. Despite his promises, Mahler’s successor did not perform the work. It was again planned in Prague in 1915, but was cancelled for budgetary reasons due to the war, and did not premiere until 1980 in Nuremberg.

While he felt frustration and even profound resentment over these circumstances, Zemlinsky always seemed reluctant to promote his own works. During his first five seasons in Prague, he only performed Es war einmal… (Once upon a time…) twice, despite the fact that it was the only contemporary opera in the theatre’s repertoire.

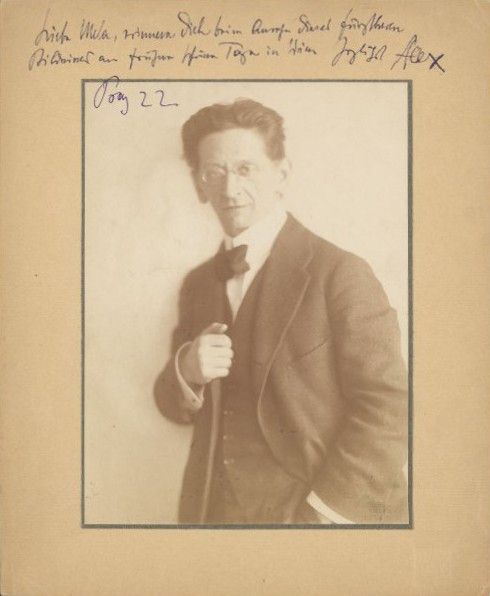

He did, however, conduct Mahler’s Eighth Symphony in March 1912, although that performance too was nearly cancelled when the Prague Aryan Choir refused at the last minute to sing Jewish music conducted by a Jew in a theatre run by a third Jew (Heinrich Teweles, was its director).

Zemlinsky asked for help from his old friend at the Vienna Conservatory, Franz Schreker (1878-1934), who had founded the Philharmonic Choir five years previously. One hundred and ten of Schreker’s choir members arrived in Prague two days before the performance, which was a triumph. They are seen posing on the steps of the Neue Deutsches Theatre, with Ida standing in the front row near Zemlinsky, Schreker, and Schönberg, who regularly visited Zemlinsky and advised him to remain in Prague.

In 1921 Zemlinsky also conducted Schönberg’s Gurrelieder, which Schreker had premiered in Vienna in 1913. A photograph commemorating the event includes the signatures of Louis Laber, the stage manager, Viktor Ullmann, the répétiteur Schönberg had recommended, and Heinrich Jalowetz, who had been Zemlinsky’s student in Vienna and later worked as a musicologist. The following year Zemlinsky became the musical director of the Musikverein in Prague; Schönberg was appointed as its president. Together the two men strove to prolong their musical projects in Vienna. Zemlinsky’s reputation as an outstanding conductor had by this time spread beyond the borders of Bohemia.

“The Zemlinsky Era”

“I think that of all the conductors I have heard I would nominate Alexander von Zemlinsky as the one who achieved the most consistently high standards. I remember a Marriage of Figaro conducted by him in Prague as the most satisfying operatic experience of my life.”

Igor Stravinsky, Themes and Episodes, 1966

When Zemlinsky’s neighbour in Prague, the music critic Leo Schleissner (1895- c. 1942), wrote in 1925 that the city had been living through “The Zemlinsky Era” for the last fifteen years, he was referring to the conductor’s strong influence on the musical life of the Czech capital. A review of the works he premiered there shows the extent of his activities and how demanding they were. For example, when Bayreuth relinquished its monopoly on Wagner’s Parsifal on 1 January 1914, Zemlinsky and his director rushed to stage it. They even rescheduled its premiere an hour earlier than originally planned, so that the Neues Deutsches Theatre would be the first in Prague to perform the work, one hour ahead of the Czech National Theatre!

At the end of the same month, Zemlinsky introduced Schönberg’s Orchesterlieder op. 8 to the audiences of Prague. The following year he turned to Djamileh by Georges Bizet (1838-1875). In 1916 he conducted two operas, The Ring of Polykrates and Violanta, both by his former student, the prodigy Erich Korngold (1897-1957), who was only nineteen at the time, as well as Mona Lisa by Max von Schillings (1868-1933), who would premiere Zemlinsky’s A Florentine Tragedy in Stuttgart in 1917 (although Zemlinsky did not care for his interpretation). Other operas Zemlinsky conducted include Cain and Abel by Felix Weingartner (1863-1942) in 1917, The Dead Eyes by Eugen d’Albert (1864-1923) in 1919, Schönberg’s Gurrelieder in 1921, and the world premiere of The Wait in 1924. He also premiered Three Fragments from Alban Berg’s Wozzeck a few months before the world premiere of the complete work. Zemlinsky ended his Prague period in 1927 with an outstanding and soon-to-be controversial opera, Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Strikes Up) by Ernst Krenek (1900-1991), one of Schreker’s former students.

Although Zemlinsky delegated more and more throughout the years, his intense activity meant that he was omnipresent in the orchestra pit, where Louis Laber, his stage manager, recalled that he sang one role after another from the podium, another way of spreading his strangeness everywhere. The thing that most struck audiences, critics, friends, and musicians about Zemlinsky was the extreme precision of his conducting and performances. Several terms, some of them synonyms, appear again and again, even when referring to scores with the most difficult reputations: exactitude, objectivity, transparency, clarity, limpidity…

His own works feature the same fluidity as his interpretations. Paradoxically, one must search among his strong points to understand why Zemlinsky was forgotten after World War II. In retrospect, the exactitude of his performances and his dramatic precision resemble the music of Hollywood films, of which Korngold was the most important composer from the 1930s on.

While Zemlinsky’s music is not cinematographic, even in the way that Korngold’s is, the listener cannot help but recognize elements that sound familiar but belong to a far-off era of film history. A woman who heard the first notes of a concert of Zemlinsky’s music in New York in 1979, when the composer had become unknown, murmured “Movie music?” to Harold Schonberg (1915-2003), the music critic of the New York Times.

Even during his glory days in Prague, however, Zemlinsky was haunted by the profound feeling known as “Sehnsucht” in German. In his case this was an aching and sometimes violent nostalgia for the city of Vienna. From the time of his arrival in Prague he exposed his feelings to anyone who would listen; Alma Mahler, Arnold Schönberg, and particularly the music critic Richard Specht (1870-1932), who did not include Zemlinsky in an article entitled “The composers of young Vienna”. For once the composer wrote to Specht, asking him to explain this omission. “Am I not Viennese?”, he queried. He was indeed and would remain so, that much is certain. But after Prague he would next turn to the recently built Kroll Opera in Berlin.

The Munich Experience

This episode, brief and little known though it is, was decisive in Alexander Zemlinsky’s career. In the summer of 1911, just before going to Prague and instead of going on vacation as he usually did, in order to be a “summer composer” (as Alain Perroux put it) like Mahler and Schreker, Zemlinsky accepted an invitation to the recently inaugurated Künstlertheater in Munich. This “art theatre” quickly rose to the forefront of German avant-garde theatre and opera productions, before the Nazis transformed it into a venue for variety shows and an Allied bombing destroyed it in 1943.

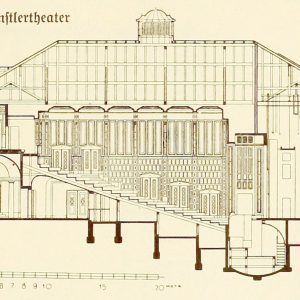

Cross-sectional view of the Munich Künstlertheater, and photo of the same building’s concert hall (1912).

Images from the book München und seine Bauten (Association of Bavarian Architects and Engineer)

Zemlinsky staged two works by Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) in Munich, Orphée aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld) and La Belle Hélène (The Beautiful Helen), and would later reprise them at the Krolloper in Berlin. It was in Munich that Zemlinsky met the conductor Otto Klemperer (1885-1973), who would become the director of the Kroll Opera when it reopened in 1927, and the stage director Max Reinhardt (1873-1943), who was responsible for the world premiere in 1906 of the staged version of Oscar Wilde’s A Florentine Tragedy, as well as a new version of La Belle Hélène that was entirely revamped by Erich Korngold, Zemlinsky’s former student.

Zemlinsky’s Munich experience introduced him to a new, modern vision of theatre and opera, or perhaps reinforced the path he was already following. There is no doubt that he was able to make use of his Munich experience in Prague, and that he took his commitment to a higher level in Berlin, where he met Otto Klemperer.