The Russian Seasons

in Paris (1906-1929)

The Russian Seasons

1906-1929

The Judgement of Paris

“To appear and be appreciated in Paris seemed to us to be the height of happiness and a definitive consecration. To know the opinion of Parisians seemed to us the best and most subtle of lessons.

Alexandre Benois, “Serge de Diaghilev”, La Revue musicale (1930).

After separating from Mir Iskusstva, Diaghilev pursued his personal exhibition projects. In 1905, he presented an impressive selection of Russian portraits from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Saint Petersburg. Although the success of this exhibition enabled him to regain the confidence of the authorities, the uncertain political climate did not favour the development of his artistic project. The turmoil and social unrest that led to the 1905 revolution, and the consequences of the defeat of the imperial troops in the Russo-Japanese war, ruined the Russian economy, which was now dependent on foreign aid. Against the backdrop of the famous Russian loans and the diplomatic rapprochement between the Empire and France, Franco-Russian artistic initiatives were encouraged. The cultural ferment in Paris, which affected all areas of creativity (music, painting, literature…), naturally attracted Diaghilev and his friends and collaborators.

Étienne and Louis Antonin Neurdein, View of the Alexandre III Bridge in Paris, at the Universal Exhibition, 1900. Source: INHA.

On the strength of his previous experience, Diaghilev organised an exhibition of Russian art in Paris at the Grand Palais, as part of the Salon d’Automne in 1906. For this first event, he relied on the collaboration of his friends Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois. True to his principles, Diaghilev highlighted the past and future of Russian art – icons and the work of contemporary painters – revealing to the public the representatives of Mir Iskusstva and ignoring the more academic currents. The resounding success of this exhibition, placed under patronage of the Grand Duke Vladimir (1847-1909), opened the doors to Parisian social and artistic circles. These “refined, disinterested, highly cultured and keen” minds, according to Benois, helped Diaghilev and those close to him to establish themselves firmly in Paris.

Thanks to this new support, Diaghilev immediately thought of organising a festival of Russian music in Paris for the following May. The “Five Historical Russian Concerts” combined instrumental works with excerpts from Russian opera arias, sometimes in the presence of or with the participation of their authors. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1848-1908), Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936), Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) and Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) travelled specially to France at Diaghilev’s invitation to attend this event. The concerts were given by exceptional performers: bass Feodor Chaliapin (1873-1938), soprano Félia Litvinne (1860-1936) and conductor Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922). This first experience led to the seven gala performances in 1908, when Diaghilev gave a dazzled audience Boris Godunov by Mussorgsky (1839-1881). On the back of the success of these first three “Russian seasons”, Diaghilev embarked on a new artistic adventure that would make him famous: the Ballets Russes.

The Ballets russes (1909-1929)

“From opera to ballet is but a step”

Diaghilev to Lifar (1928).

Although in his youth Diaghilev did not share the enthusiasm of his Pickwickians friends for the world of dance, time and exchanges with his comrades led him to change his point of view on this art form. In October 1896, he wrote to Benois: “Valitchka [Walter Nouvel] is unbearable with his ballet”, but five years later he supported a new production of the ballet Sylvia by Léo Delibes (1836-1891) at the Théàtre impériaux. However, this first experience, encouraged by his friends Benois, Korovin, Lanceray, Bakst and Serov, enabled Diaghilev to spot among the young dancers those who were making their mark against “the classical tradition, which Petipa so jealously preserved”. From then on, he thought about the possibility of “[creating] a number of short new ballets, which besides being of artistic value would link the three main factors, music, decorative design, and choreography far more closely than ever before” (Lifar).

The new contacts established with Parisian social circles would encourage this venture. The first performances of the Ballets russes at the Théâtre du Châtelet were made possible thanks to the unfailing support of impresario Gabriel Astruc (1864-1938). The patronage of salonnières such as the Countess Greffuhle (1860-1952) and Misia Sert (1872-1950) was invaluable when it came to attracting the support of the great Parisian fortunes of Count Isaac de Camondo (1851-1911), Baron Henri de Rothschild (1872-1947), Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe (1846-1919) and others: “There was […] a desire for true luxury and complete opulence, […] refinements of every kind; a generous absence of all poverty, of all economy”, recalled one of the first spectators, Emile Henriot.

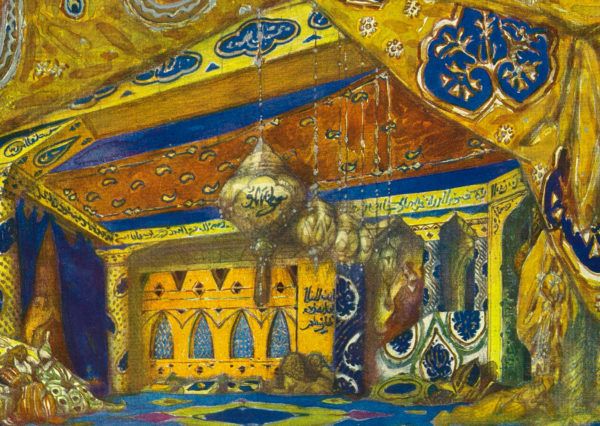

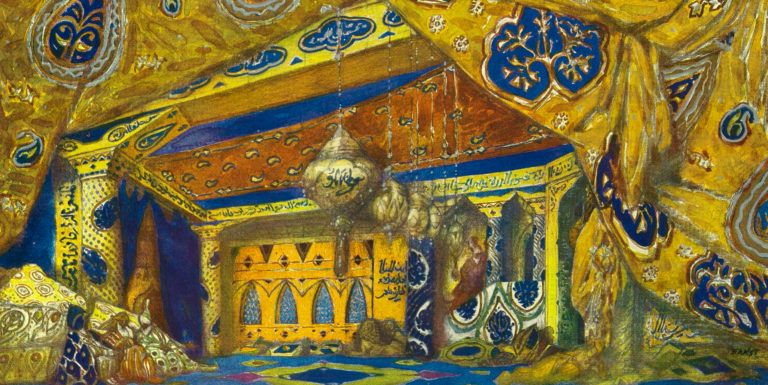

Léon Bakst, sets for the ballet Les Orientales, 1910. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF.

As Diaghilev conceived it, each show featured between three and five ballets presented in succession. Certain creations that were close to the great classics (Giselle, Swan Lake, Les Sylphides) were an immediate success (the Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor, Petrushka, Scheherazade). Diaghilev did not hesitate to associate The Rite of Spring, a disconcerting work in terms of its argument, music and choreography, with the romantic Sylphides or The Spectre of the Rose. During these twenty years of French productions (with two interruptions in 1916 and 1918), the company gave around 295 performances and had more than 70 ballets in its programmes.

Works most often associated within the same evening. String diagrams generated with Datasmith, © 2023 Ben Peterson.