Collaboration

between Artists

Collaboration

between Artists

What Orient is about?

“(…) when I am producing a ballet, I never for a moment lose sight of one of these factors [music, dance, sets]. Thus, I often visit the scene-painting studios, the sewing-room, attend orchestral rehearsals, and every day visit the production studio to watch my artists at work, from the stars to the boys in the corps de ballet, completing their training.”

Diaghilev to Lifar (1928).

Until the First World War, the success of the Ballets Russes was based mainly on the collaboration of strong artistic personalities: Fokine, Stravinsky, Bakst and Benois. The repertoire of the early seasons sought to strike a balance between tradition and modernity, with Fokine’s revised choreographies of the ballets performed in Saint Petersburg rubbing shoulders with creations that evoked an Orient that was by turns bewitching or barbaric.

Michel Fokine (1880-1942) ensured the early success of the Ballets Russes’ first seasons with his innovative choreography. Engaged as a principal dancer at the Mariinsky Theatre as soon as he finished his studies, he developed a double activity as a choreographer and ballet master. His approach to teaching was innovative. “I tried to give meaning to the movements and poses; I tried not to make dance resemble gymnastics”. In 1909, Fokine left his position at the Mariinsky Theatre and became the official choreographer of Diaghilev’s company until he left in 1912. His approach was based on a return to the essentials of movement in order to spark genuine emotion in the spectator. His ballets were conceived as a continuous whole, achieving a symbiosis between libretto, music, sets and costumes. During the first seasons, Fokine worked mainly with Bakst (Scheherazade, The Spectre of the Rose, Daphnis et Chloé, Thamar, Le dieu bleu) and Benois (Le Pavillon d’Armide, Les Sylphides, Petrushka).

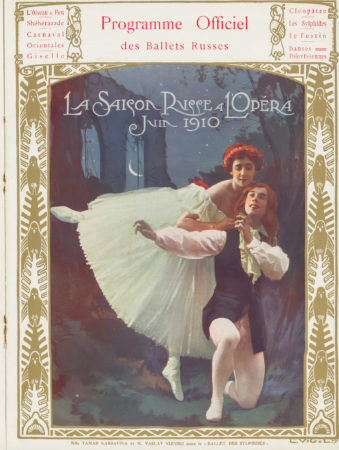

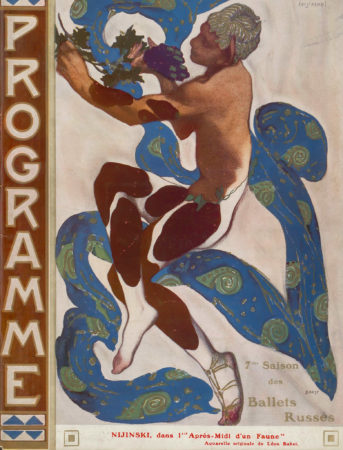

Two illustrations from the official programmes from the 1910 season in Paris. On the left: Tamara Karsavina and Vaslav Nijinsky in Les Sylphides. On the right: Léon Bakst illustration of the Shah of Persia, from Scheherazade.

But the choreographer would be nothing without his dancers… Three artists stood out in the company’s early years: Enrico Cecchetti (1850-1928), who trained the company’s stars and remained a close adviser to Diaghilev throughout his life; Tamara Karsavina (1885-1978), creator of Fokine’s ballets; and her occasional partner Vaslav Nijinsky (1890-1950). Nijinsky, who was very popular with the Parisian public, gradually became the company’s most sought-after star, being entrusted with the choreography of L’Après-midi d’un faune (1912), Jeux (1913) and Le Sacre du printemps (1913), thus dethroning Fokine. This change also reflected an aesthetic turning point for the company. Indeed, while the success of the first seasons was closely linked to the evocation of oriental charm or its barbarism – a field in which the Fokine-Bakst duo excelled – Diaghilev, wanting to escape all forms of routine, sought to renew his programmes with daring artistic proposals. Nijinsky’s Dalcroze-inspired choreography was not universally acclaimed, but it gave the company new visibility, if only through a few scandals.

"Astound me!"

“For I had come by now to realize that [Diaghilev] valued his collaborators only as long as, in his view, they had something new to contribute.”

Serge Grigoriev, The Diaghilev Ballet (1953).

“Astound me” was the imperative that Diaghilev imposed on his collaborators. But beyond this injunction, the consequences of the war and the successive departures of Fokine and Nijinsky forced Diaghilev’s troupe to reinvent itself. New members were integrated into the company, including Léonide Massine (1896-1979), an actor and dancer who had already made a name for himself with his performance in La Légende de Joseph. He choreographed Soleil de nuit (1915, with Bakst), Les Femmes de bonne humeur (1917, also with Bakst) and La Boutique fantasque (1919, with Derain), as well as Parade, The Three-Cornered Hat and Pulcinella (with Picasso in 1917 and 1920). According to Pierre Michaut, he offered an opening onto “the old forms of dance and […] the burlesque vein“. Of all his works, the most remarkable was undoubtedly Parade, which, despite a rather cool reception at its premiere (1917), already anticipated the post-war aesthetic. Here, in the words of Guillaume Apollinaire, Massine bent “in a surprising way to Picassian discipline”, achieving a form of “sur-realism“.

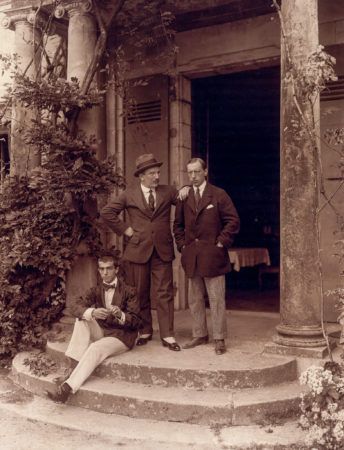

Léonide Massine, Léon Bakst et Igor Stravinsky in Lausanne, 1915. Photo: James Perret (?). Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF.

After the war, the Ballets Russes renewed themselves through collaborations with French composers such as Francis Poulenc (1899-1963), Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) and Georges Auric (1899-1983), who worked closely with Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Juan Gris (1887-1927) and Georges Braque (1882-1963). But Stravinsky, now on good terms with Diaghilev, also signed several works. This new phase was marked by the creations of Bronislava Nijinska (1891-1972), Vaslav’s sister and Massine’s replacement, who had left the company in 1921. Renard (1922), Noces (1923), Mavra (1922), Le Train bleu (1924), Les Biches (1924) and Les Fâcheux (1924) date from this period. The choreography of these highly technical ballets was appreciated for its “cleverness” (Stravinsky) and “beauty” (Poulenc).

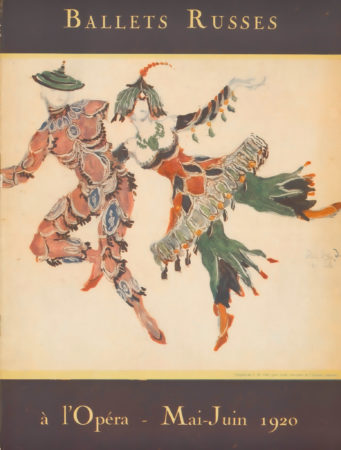

Two illustrations from the official programmes. On the left: Picasso’s “Chinois” design costume from Parade (1917). On the right: two costumes by J.M. Sert for Astuce feminine (1920).

The last years of the company were marked by the return of Massine and the arrival of George Balanchine (1904-1983) and Serge Lifar (1905-1986). Their choreographies contributed to a new direction for the Ballets Russes, more in keeping with the spirit of the “Roaring Twenties“. Diaghilev called on G. Auric, Henri Sauguet (1901-1989) and Serguei Prokofiev (1891-1953) to set the music for this new chapter in the company’s history. However, times had changed and the artistic landscape was no longer the same as it had been in the early days of the company. The Ballets Suédois were imposing serious competition on the Ballets Russes and, tired and weakened, Diaghilev died in Venice in the summer of 1929.