Before the Ballets:

the Russian soul

Before the Ballets:

the Russian soul

A Certain Determination

“What is indisputable is the presence, in this still young man, of colossal faith in himself and – what, for a Russian, is quite astonishing – an endless reserve of energy, an inexhaustible inventive spirit, and tenacity in carrying out his projects. All in all, an absence, against all odds, of the slightest weariness, complaint or disappointment”.

Vasily Rozanov on Serge Diaghilev.

It has often been said that Diaghilev was not, in the true sense of the word, a “creator”. Some even speak of a “failure“: as a singer, as amusician and as a composer. Despite his enthusiasm and commitment to music, his attempts at composition were not recognised by those close to him. However, in the 1890s, thanks to the support of his Petersburg friends, mainly Benois and Bakst, he “combined his musical knowledge with a genuine enthusiasm for art“. As J.-M. Nectoux observed, he “[acquired] with astonishing rapidity an ‘eye’ which, later on, always made him distinguish the greatest artists in the youth of their art“. This natural talent for observation, combined with his innate organisational skills, soon made him a major player and producer in artistic life in Saint Petersburg. As a result, he developed an intense activity both in the written word (through his art reviews and chronicles) and in the exhibitions he organised. The articles published in the press during this period reflect his character: demanding and passionate (even vehement), but always driven by a search for what he believed art should be.

(Russian) Art first and foremost

“Russia then lived on memories and walked in the shadow cast by its past. Memories […] of a disintegrating society that […] took refuge in what was. […] [What Diaghilev] wanted was for Russia to become aware of itself, of its riches, of its virtues, particularly in the intellectual field, and for it to bring its past to life by making closer contact with the present and taking its place in it”.

Robert Brussel, “Avant la féerie”, La Revue musicale (1930).

During the 1890s, Diaghilev’s many journeys throughout Europe, rich in exhibition visits and meetings with artists, made him aware of the “inward-looking” state from which Russian art was then suffering. In one of his first chronicles dating from 1896, borrowing from military vocabulary, he encouraged the adoption of a two-fold strategy: to regain the ground lost by Russia and to collaborate in the development of a universal art. “We must charge straight ahead. We must strike without fear, impose ourselves at once, reveal ourselves completely with all the qualities and defects of our national character”, exclaimed Diaghilev. This offensive stage would be followed by concord, a time of “solidarity” and exchange between the European and Russian arts, “both in the form of active participation in the life of Europe and in the form of an invitation to European art to come and perform here“.

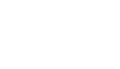

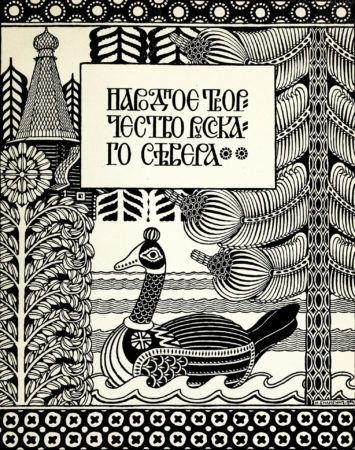

Illustration by Ivan Bilibin and photograph of traditional fabrics in the article “Folk Arts and Crafts in the North of Russia”, Mir Iskusstva, 1904.

The following year, faithful to this line of conduct, Diaghilev organised his first exhibition devoted to English and German watercolourists in the hall of the Stieglitz Museum in Saint Petersburg. The exhibition, conceived as an expression of personal choice, was anything but an “elegant event”, as Alexandre Benois pointed out. “This absence of any ideological programme, this emancipation from a utilitarian doctrine”, emphasised the painter, “unleashed acerbic criticisms of the prevailing ideas“.

This first exhibition at the Stieglitz Museum was to be followed by others, notably the one in 1898 consacrated to Russian and Finnish painters, which enabled Diaghilev to bring together both renowed and novice artists (including his friends Bakst, Benois and Somov). Each of these events was an opportunity for Diaghilev to raise awareness in social circles of a current of artistic renewal. It was an approach that J.-M. Nectoux sees as “[a] very personal concern to combine innovation and worldliness, the one financing the other and ensuring its success, which would be implemented throughout Diaghilev’s activities in favour of Russian opera and ballet”.

Mir Iskusstva : World of Art

“At the moment I am busy creating this review, in which I intend to bring together all our artistic life, that is to say, to show real painting in the illustrations, to say frankly what I think in the articles, and then to organise a series of annual exhibitions in the name of the review…”.

Diaghilev to Benois, 8/20 October 1897

Diaghilev quickly realised the need to rally all those who shared his project to unveil and renew Russian art. This collective action made it possible to respond to criticism from academic circles, in particular through the publication of a magazine and the staging of regular exhibitions. Born out of the Nevsky Pickwikians, the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) group mainly brought together painters, decorators and illustrator from Saint Petersburg and Moscow, recruited by Benois and Diaghilev. The group soon expanded to include Eugene Lanceray (1875-1946), Mstilav Dobuzhinsky (1875-1957), Valentin Serov (1865-1912), Konstantin Korovin (1861-1939), Aleksandr Golovin (1863-1930), Boris Kustodiev (1878-1927), Filipp Malyavin (1869-1940), Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942), Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947)… all artists who will lend their support to the “Russian Seasons”.

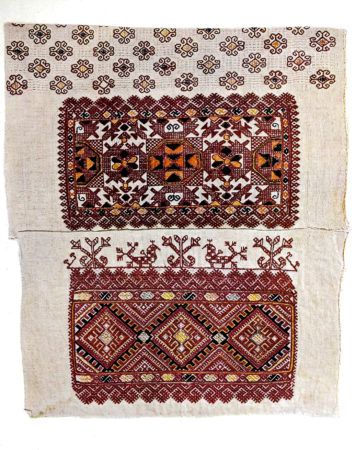

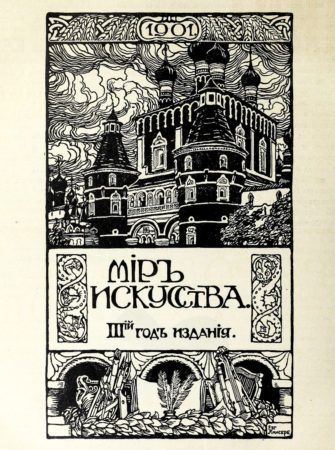

Covers and flyer for the magazine Mir Iskusstva. From left to right: cover signed by Maria Yakunchikova (1899, nos. 13-14), cover by Léon Bakst (1902, no. 7) and prospectus by Eugène Lanceray for 1901. The latter illustration was used in the programme for the “Cinq Concerts historiques russes” in Paris in 1907.

Mir Iskusstva was first published in November 1898, with the financial support from Princess Maria Tenisheva (1858-1928) and the industrialist Savva Mamontov (1841-1918). But like other publications of its kind (La Revue blanche, The Yellow Book, Pan or Ver Sacrum), Mir Iskusstva‘s life was short-lived, with the last issue appearing in 1904. Richly illustrated, sometimes with colour plates, this magazine showed a Francophile inclination. The two miriskusniki, Alfred Nurok and Charles Birlet, who, according to Avril Pyman, closely followed French literary news and the Impressionist movement, were particularly enthusiastic about it. The summaries of Mir Iskusstva, in Russian and French, illustrate Diaghilev’s openness to European art: Whistler, Huysmans, Grieg, Degas, Ruskin and Maeterlinck rub shoulders with Pushkin, Tolstoy, Solovyov and Wolkonsky.

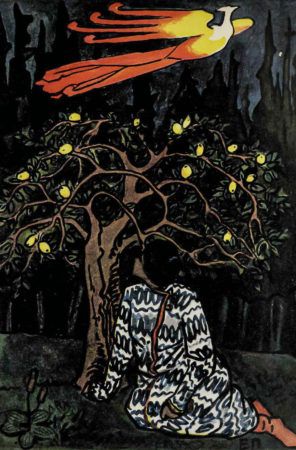

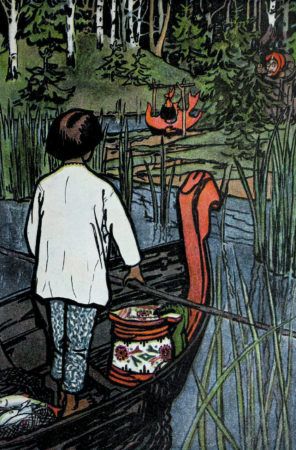

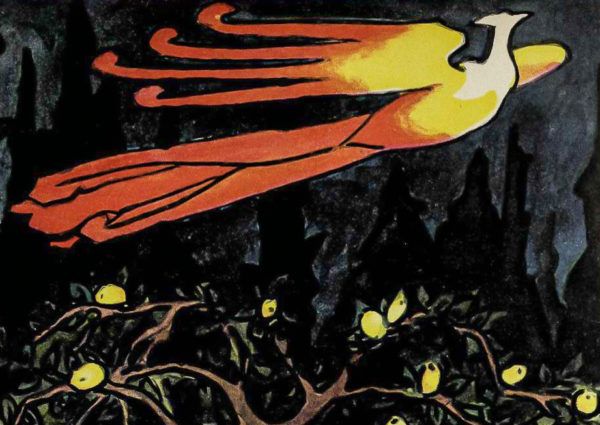

Two illustrations by Elena Polenova for traditional tales. On the left, The Firebird, on the right, The Story of Synko-Filipko (Mir Iskusstva, 1899 and 1900).

Although economic difficulties, polemics and internal conflicts led to the inevitable break-up of the group in 1904, after only three exhibitions, this experience enabled Diaghilev to expand his network and sow the seeds of the future “Russian Seasons” in Paris.