Analyses

Vienna, The Femme Fatale

and the “Tragedy of an Ugly Man”

Vienna, The Femme Fatale

Analyses

and the “Tragedy of an Ugly Man”

A certain common aesthetic brings together French Symbolism, English Pre-Raphaelite painting, and the artists of the Viennese Secession. They shared a similar vision of women, whom they of course assumed to be femmes fatales, and whose long, flowing hair was an easily recognized sign. In Viennese cafés men did not mingle with women, when they happened to be present. Men fantasized about women, and feared them. The prevailing opinion presumed that women were so inclined to lust that only the most rigorous education could rein them in. It was believed that once a woman had had sexual relations, her social reputation could never been recovered.

These notions, combined with anti-semitic theories, produced one of the most famous essays of early-twentieth century Vienna: Sex and Character, by Otto Weininger (1880-1903), whose success increased after the young author committed suicide. In Weininger’s view, “the Jew” suffered from the same spiritual and moral deficiencies as “the woman”. The equally young essayist and future scriptwriter Georg Klaren (1900-1962), who wrote a monograph on Weininger in 1924, adapted The Birthday of the Infanta to Weininger’s theses.

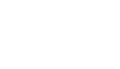

Although Zemlinsky probably shared these views, his interest was more in the “tragedy of the ugly man”, as he described it to Schreker as early as 1909. Indeed, the previous year, at the request of the sisters Elsa and Grete Wiesenthal, Zemlinsky had composed the music to a ballet based on Oscar Wilde’s The Birthday of the Infanta, which was presented at Klimt’s Kunstschau. Schreker had collaborated with Zemlinsky on the work, but dropped the project in order to better concentrate on his own version of the story, which resulted in the opera The Stigmatized in 1918. The theme and the period – sixteenth-century Genoa – were in fashion, as was Wilde, one of whose aphorisms featured in the introduction to the painting section of the 1908 Secession catalogue: “Art”, it read, in a disavowal of any underlying message, “never expresses anything but itself.”

Oscar Wilde,

Alexander Zemlinsky , and

the Aesthetics of Ugliness

Oscar Wilde,

Alexander Zemlinsky and

the Aesthetics of Ugliness

“Music always seems to me to produce that effect. It creates for one a past of which one has been ignorant, and fills one with a sense of sorrows that had been hidden from one’s tears.”

Oscar Wilde, The Critic as Artist, 1891

In 1892 Max Nordau (1849-1923), a doctor, and with Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) the co-founder of the World Zionist Organization, published Degeneration. This essay points out the features of fin-de-siècle art – which would become the degenerate art of the Nazis – that were symptomatic of the generalized decadence that was overtaking Paris, Vienna, and London. Some of his targets were Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900).

Wilde had written (in French) his tragedy, Salomé, the previous year. The London censors banned its performance on the grounds that the depiction of Biblical characters was unlawful. When it premiered in Paris in 1896, Wilde was already serving a prison sentence for homosexual activity, thereby becoming a symbol of persecuted genius throughout Europe. Four years after Wilde’s death, Richard Strauss adapted Salomé for the opera, but it was banned at the Hofoper and then in Berlin for the same reason as in London. It finally premiered in Graz in the spring of 1906 in a private theatre – with Zemlinsky in the audience. In the autumn of the same year, Max Reinhardt produced the play in Berlin.

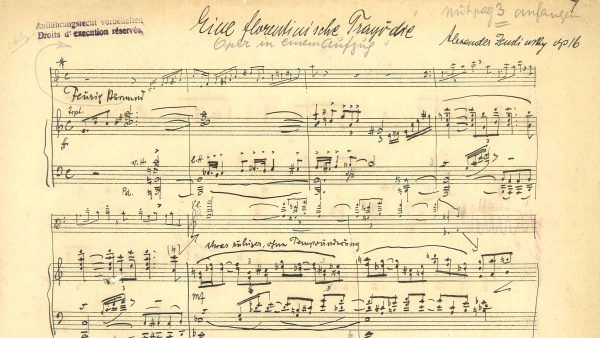

Reichardt had premiered Wilde’s A Florentine Tragedy in January 1916. Zemlinsky adapted the short, one-act play the same year, but it was only performed five times in Prague. His version respected the time frame of Wilde’s play – a single evening – the place – a Florentine dwelling belong to Simone, a merchant – and the action: Simone surprises his wife Bianca with the prince Guido Bardi. He pretends not to understand, argues, attempts to sell his wife, challenges the prince to a duel, and finally strangles him.

This tripartite unity is immediately shattered by the outbreak of savagery, as were the three characters from the outset, each pretending to act out a comedy that ends badly. The violence of the murder cancels out any glow of romanticism the play might have contained, and it is hard to say whether Wilde raised a sordid news item to the level of tragedy, or on the contrary lowered tragedy to the level of a news item.

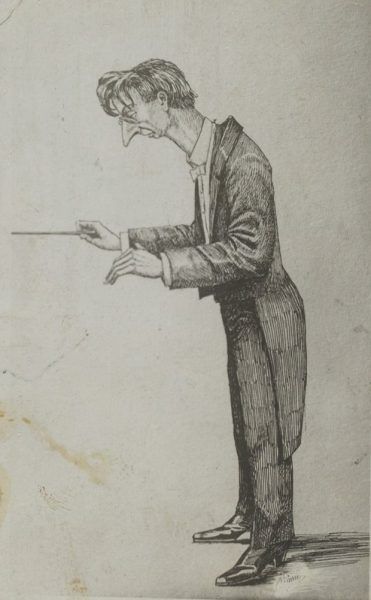

The Dwarf, written by Wilde in 1891 and second of his works adapted by Zemlinsky, contains similar violence mixed with even greater cruelty. The décor, inspired by Las Meninas by Diego de Velázquez (1599-1660) heightened this effect. The luxurious decadence of the Spanish Golden Age echoed that of the British Empire, and also resonated with the current situation in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Infanta, who is celebrating her birthday, is given a hideous dwarf as a present. The dwarf is unaware of his ugliness, and falls in love with the Infanta. But when he sees himself in the mirror for the first time, he gives a wild cry and dies of terror and furious disappointment.

His cry rends the play with the same force as the last breath of the strangled prince, who was asphyxiated by the merchant’s malediction. In both cases Zemlinsky’s music borders on the obscene, and seems to hurl insults at beauty. Perhaps there is more here than a simple identification of the author with the Dwarf, although the ugly little man (who Zemlinsky makes stateless) was indeed a recurring figure in his work.

Georges Starobinsky suggested that by thematizing ugliness Zemlinsky allowed himself to push the boundaries of beauty and thereby to create new musical forms. In other words, the theme of ugliness enabled Zemlinsky to address a certain aesthetic modernity stemming from realism. But like in the work of Wilde and Hofmannsthal, this depth was hidden beneath the attire of eclecticism, and dissembled in the places where it was least apparent.

Alexander Zemlinsky

as seen by Theodor Adorno

Alexander Zemlinsky

as seen by Theodor Adorno

In his article “Alexander Zemlinsky”, published in 1959 and included in the collection Quasi una fantasia, printed in 1963, the philosopher, musicologist and sociologist Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) was one of the very first to attempt to do justice to Zemlinsky’s work. A great admirer of Arnold Schönberg, in whose shadow Zemlinsky is often placed, Adorno demonstrated that too little attention had been paid to Zemlinsky’s musical intelligence and modernity, and that in the end he returns the accusation of eclecticism that was so long leveled against him.

“It is such bewildering considerations as these which give one pause when the accusation of eclecticism makes its premature appearance. The distinction to be made instead is between the secondary talent and the artist who has something to express, even if it is only the crisis of art. Alexander Zemlinsky, who originates from the same spiritual ambience as Mahler, made more of the compromises characteristic of the eclectic than any other composer of rank of his generation. […] But his eclecticism shows genius in its truly seismographic sensitivity to the stimuli by which he allowed himself to be overwhelmed.”

“In his mature works as a composer je came closer than anyone to the ideal of distilled comedy: subtle and not overloaded with meaning, an ideal Hofmannsthal had vainly looked for in Strauss. If Zemlinsky succeeded in this it was because he had complete mastery of the means at his disposal, while possessing enough self-knowledge to remain within his limitations.”

“In certain circumstances a many may be cheated of his deserts by nothing more than a lack of ruthlessness. It is possible to be too refined for one’s own genius and in the last analysis the greatest talents require a fun of barbarism, however deeply buried.”

english translation by Rodney Livingstone (Verso, 1998)