In the Spotlight

1910: The Firebird

1910: The Firebird

In the Spotlight

In search of a composer

“I need a ballet, a Russian fairytale ballet, but you understand, for the French, for Paris. You know all the young composers here. Who, in your opinion?”

Conversation with Diaghilev reported by Boris Asafyev.

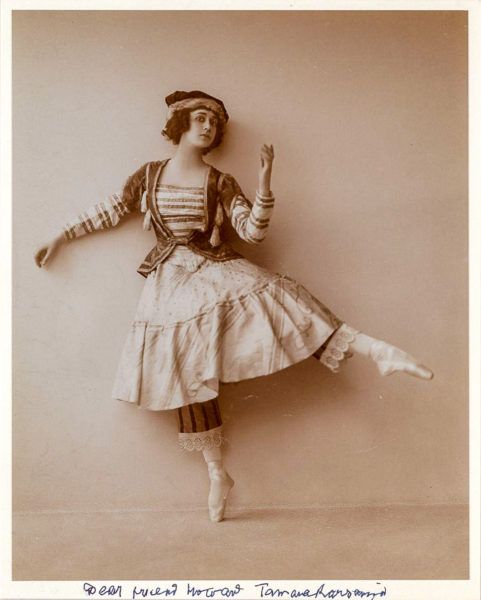

In 1909, Diaghilev was looking for a composer capable of setting a fairytale ballet inspired by a traditional tale to music. Two names were approached: Nikolai Tcherepnin (1872-1945) and Anatoly Lyadov (1855-1914). In the end, the commission went to the young Stravinsky. Completed on 18 May 1910, barely a month before the premiere, the style of the score disconcerted the dancers: Anna Pavlova (1881-1931) refused the role of the Firebird, while Tamara Karsavina (1885-1978) “only managed to take it on with Stravinsky’s help, tirelessly rehearsing passages of his score on the piano”. The first audiences were captivated by the harmonic richness of Stravinsky’s music, so much so that the critic Henri Ghéon exclaimed: “Compared to The Firebird, Scheherazade feels a bit of an adaptation”.

About The Firebird

Russian fairy tale in 2 tableaux by Mikhail Fokine.

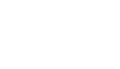

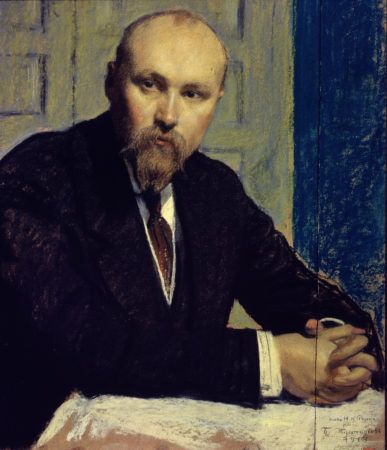

Music by Igor Stravinsky. Choreography by Michel Fokine. Sets by Alexandre Golovin, executed by Sapounov and Charbey; costumes by Alexandre Golovin and Léon Bakst (The Firebird, Ivan Tsarevich, the Beautiful Tsarevna) executed by Caffi. Regie by Serge Grigoriev.

First performed in Paris, at the Théâtre de l’Opéra, on 25 June 1910, conducted by Gabriel Pierné.

Principal performers: Tamara Karsavina (the Firebird), Vera Fokina (the Beautiful Tsarevna), Michel Fokine (Ivan Tsarevich), Alexis Boulgakov (Koschei).

Synopsis

One day, Ivan Tsarevich sees a marvellous bird all in gold and flame; he pursues it but is unable to seize it and only succeeds in plucking one of its glittering feathers. His pursuit leads him into the domain of Koschei the Immortal, the fearsome demigod who wants to take him over and turn him to stone, as he has already done to many a prince and many a valiant knight. But Koschei’s daughters and the thirteen princesses, his captives, intercede and try to save Ivan Tsarevich. The Firebird arrives and dispels the enchantments. The castle of Koschei disappears, and the young girls, the princesses, Ivan Tsarévitch and the freed knights take possession of the precious golden apples in his garden.

In her memoirs, Karsavina recounts the sessions with the painter: “His sense of the picturesque he said was curiously amused by the slender structure of my facial bones an the unexpected vigour of my neck. To bring out this peculiarity he had long studied me, finally deciding on the turn of the head, which seems to me gives something imperative to the pose of the Firebid which he had chosen.”

1911: Petrushka

1911: Petrushka

A Russian "Pierrot”

“Musically, by far the most difficult part for the dancers in this Ballet is the Finale. After the appearance of the masqueraders, the 5/8 count is played at a very rapid pace. This was so difficult to grasp that my rehearsal changed into a lesson in rhythmics, I summoned the troupe to the piano and asked them all to clap their hands. Everyone clapped, but on a different beat.”

Michel Fokine, Memoirs of a Ballet Master (1961).

During a visit to Stravinsky in Switzerland at the end of the summer of 1910, Diaghilev learned that the composer was not working on The Rite of Spring, a project that had come to him when he had finished orchestrating The Firebird. Interested in a piece for orchestra and piano, a “Concertstück“, that Stravinsky played for him, Diaghilev suggested that he turn it into a ballet. Benois proposed a carnival scene in Saint Petersburg. In his Reminiscences, the painter wrote: “the subject of the drama, the characters and development of the action and most of the details were mine, but all this seemed a mere trifle in comparison with the music. So when Stravinsky at one of the last rehearsals asked: ‘Who is the author of Petrushka?’ I answered: ‘Of course it is you.’ But Stravinsky would not agree to this and protested energetically, saying that it was I who was the real author. Our combat de générosité ended with both of us being named, and here again out of reverence I insisted on his name being placed first. My name appeared a second time in the score, for Stravinsky dedicated Petrushka to me, a fact which touched me deeply.”

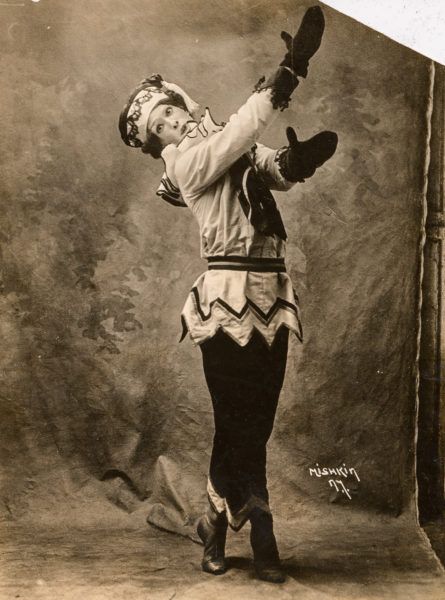

Photograph of Nijinsky in the role of Petrushka, 1911. Source: Library of Congress, Music Division.

About Petrushka

Burlesque scenes in 4 tableaux by Igor Stravinsky and Alexandre Benois.

Music by Igor Stravinsky. Scenes and dances by Michel Fokine.

Sets and costumes by Alexandre Benois; sets excuted by Anisfeld; costumes excuted by Caffi and Vorobiev. Régie by Serge Grigoriev.

First performed in Paris at the Théâtre du Châtelet on 13 June 1911, conducted by Pierre Monteux.

Principal performers: Tamara Karsavina (the Ballerina), Vaslav Nijinsky (Petrouchka), Alexandre Orlov (the Moor), Enrico Cecchetti (the Charlatan).

Synopsis

It’s Carnival time in St Petersburg. […] A Charlatan dressed as a magician announces from the top of his trestle that he is going to present animated puppets. And his trick is truly a prodigy. His dolls, Petrushka (a puppet), a Moor and a ballerina, dance with a gusto that makes them look like living creatures.

In the second tableau, we witness the intimate life of Petrushka. He dances, he dreams, he suffers. In love with the Ballerina, he is jealous of the Moor. […] In the fourth tableau, the party is in full swing. […] Suddenly the dancing and singing are interrupted by screams from the small theatre. Petrushka emerges, pursued by the Moor, whom the Ballerina tries in vain to restrain. But the furious Moor reaches out and strikes him with his sword. Petrushka falls on the ground with his skull crushed.

The audience is moved, not wanting to believe that these are dolls. The police are called and the magician is arrested. The magician calmly picked up Petrushka’s corpse, which to the audience’s astonishment turned out to be a miserable doll filled with sawdust. [But the spectre of Petrushka appears on the roof of the funfair, threatening the magician, who flees in terror].

Photograph of Tamara Karsavina as the Ballerina in Petrouchka, c.a. 1911. Source: Harvard Theatre Collection, Harvard University..

1913: The Rite of Spring

1913: The Rite

of Spring

"A beautiful nightmare”

“I still remember the performance of your Sacre du Printemps at Laloy’s. It haunts me like a beautiful nightmare and I try in vain to recall the terrifying impression. That is why I await the performance like a greedy child who has been promised sweets.”

Debussy to Stravinsky, 7 November 1912.

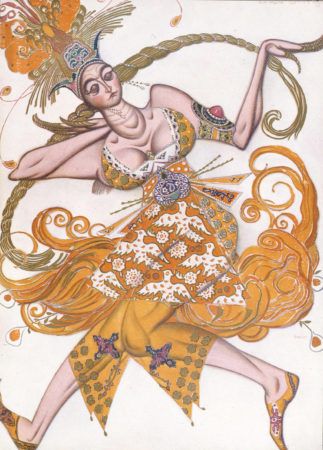

In 1931 Stravinsky declared that the idea for The Rite of Spring had come to him when he was completing the orchestration of The Firebird in May 1910. He remembered seeing in a dream the solitary dance of “a young girl in front of a group of fabulously old men, withered, almost petrified”. The argument evoking prehistoric rites of the pagan Russia, Stravinsky teamed himself with Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947), a painter, traveller and explorer, member of Mir Iskusstva, who had taken part in archaeological digs in the province of Novgorod. The influence of the past is reflected in the music. Although deliberately disimulated by Stravinsky, several folk themes infuse the score, as shown by the research of Lawrence Morton and Richard Taruskin. In all likelihood, the composer drew on traditional melodies.

As for the choreography, Nijinsky was given complete freedom. Nevertheless, the result never convinced the composer. Stravinsky, in his Chronicle, recalls: “When, in listening to music, he contemplated movements, it was always necessary to remind him that he must make them accord with the tempo […]. It was an exasperating task […]. It was all the more trying because Nijinsky complicated and encumbered his dances beyond reason, thus creating difficulties for the dancers which it was sometimes impossible to overcome”.

Much has been said about the tumultuous premiere of The Rite of Spring on 29 May 1913. However, the dress rehearsal, which was attended by numerous musicians, artists and literary figures, went off peacefully. “I was very far from expecting such an outburst”, the composer marvelled. The ballet, on the programme of the 1913 Russian seasons, was not performed again until 1920, this time with the choreography by Léonide Massine (1896-1979) created in close collaboration with Stravinsky and which did not take into account of any anecdotal detail or development.

About The Rite of Spring (1913)

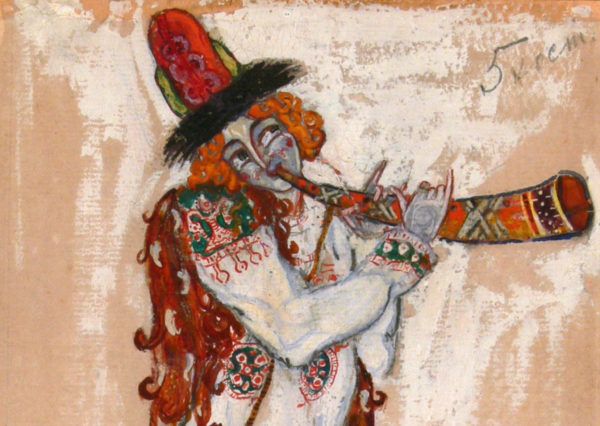

Pictures from Pagan Russia, in 2 parts, by Igor Stravinsky and Nicholas Roerich.

Music by Igor Stravinsky.

Choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky.

Set and costumes by Nicholas Roerich. Regie: Serge Grigoriev.

First performed in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on 29 May 1913, conducted by Pierre Monteux. Principal performer: Marie Piltz (the Chosen One).

Restaged in 1920, with a new choreography by Léonide Massine and Lydia Sokolova in the role of the Chosen One.

Synopsis (1913 version)

First Tableau: Adoration of the Earth

Spring. The earth is covered with flowers. The earth is covered with grass. A great joy reigns on the earth. The men begin to dance and question the future according to the rites. The Eldest of all the Sages takes part himself in the Glorification of Spring. He is brought out to be united himself with the abundant and superb earth. Everyone stamps the earth in ecstasy.

Second Tableau: The Sacrifice

After nightfall; after midnight. On the hills there are sacred stones. The young girls play mystical games and seek the Grand Way. They glorify the one who has been chosen to be offered to the Gods. They call up the Ancestors as venerable witnesses. And the wise Ancestors of the men watch the sacrifice. It is thus that they sacrifice to Yarilo the magnificent, the flaming.